Ecology of the Black Isle

What’s special about the Black Isle?

An article written by Ro Scott in April 2008 and revised for Black-Isle.info

The Black Isle from a great height

An Isle but not an island, located in the Highlands but essentially lowland in character, intensively managed but sometimes surprising in its wildness, the Black Isle is a land of contradictions and contrasts. In reality a peninsula, the Black Isle extends approximately 16 miles/25km from its somewhat arbitrary landward boundary between Beauly and Conon Bridge to its extremity at Cromarty, and measures roughly 6 miles/ 10km in width. Bounded to the north by the Cromarty Firth and to the south by the Beauly and Inverness Firths it was, until the construction of the Kessock Bridge in the early 1980s, relatively remote and isolated from the ‘mainland’ of Easter Ross. Now well within the Inverness commuter belt, it is subject to development pressures, particularly demand for housing, resulting from the city’s booming economy.

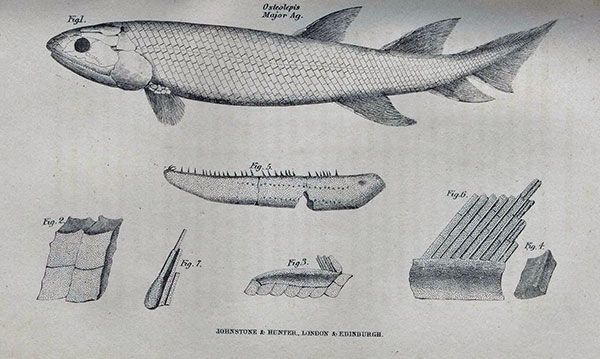

The underlying geology is predominantly Old Red Sandstone, made famous by the Black Isle’s most illustrious son, 19th Century stonemason, geologist and writer, Hugh Miller. In some localities, such as at Cromarty and Eathie, the sandstone is rich in fossil fish.

Osteolepsis drawn by Hugh Miller Collection of Ro Scott

Examples first described by Miller may be seen in the museum, run by the National Trust for Scotland, which now occupies his birthplace in Cromarty. Horizontal bedding in the sandstone gives rise to a tiered landform of short steep rises interspersed with more gently-sloping plateaux. The maximum altitude of 841ft/ 256m is reached at Mount Eagle, near to the Black Isle’s major landmark, a huge telecommunications mast. The sandstone is varied in composition with some notably calcareous layers. Soils are fertile, but not as freely-draining as one might expect because of a significant clay component. In the south-eastern corner, a band of conglomerate underlies the landfall of the Kessock Bridge and extends northwards to form the bold headlands of Craigiehowe and Wood Hill, which frame the mouth of Munlochy Bay. The South Sutor, and its companion to the North, which similarly guard the entrance to the Cromarty Firth, are composed of ancient Moine schists, which elsewhere are overlain by the sandstone. On the shore at Eathie, below the fossil fish bed, is an outcrop of Jurassic shale containing ammonite and belemnite fossils. The whole coastline from Rosemarkie to Cromarty is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) for its geology and botany, and fossil-hunters are asked to collect only from loose material on the beach, rather than hammering the rocks in situ. The combination of sandstone and sea has produced some spectacular erosion features – rock pinnacles, caves, and at MacFarquhar’s bed, further north towards Cromarty, a huge sea-arch.

McFarquhar's Bed Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

McFarquhar's Bed Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

Remnants of glaciation are more visible around the coast than inland. The cliffs along the south-eastern coast are set back from the sea by a raised beach – which makes for easy walking along the shore. Chanonry Point, jutting out into the Moray Firth from Fortrose, is the top of a huge bank of morainic material which nearly blocks the Firth, leaving only a 1km wide tide-race gap between the Point and Fort George on the other side.

The maritime influence and relatively low altitude give the Black Isle a milder and more equable climate than the more mountainous mainland surrounding it. With an annual rainfall averaging between 25 and 40”/600 to 1,000mm it is one of the drier parts of Scotland. The fact that the Black Isle remains snow-free, when the hills around are white, is thought to be one potential explanation for its name. (Another is that it is a conflation or confusion of ‘dubh’, the Gaelic word for black, and ‘Duthac’, the name of a local saint.)

Because of its relative fertility, benign climate and easy accessibility by sea, the Black Isle has a very long history of human occupation. Along the south-eastern shore, which parallels the Great Glen Fault, previous occupants have left shell middens outside their cave shelters at the base of the cliffs. Inland, Bronze Age cairns and Viking and Pictish remains testify to early settlement by farming peoples. Fortrose, with its now-ruined cathedral, was described in 1693 as “the seat of law, divinity and physic”. This long-vanished ecclesiastical settlement has left its own legacy of medicinal plants which still survive in the local flora.

Farmland near Culbokie Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

Land use now consists of smaller farms and crofts raising livestock towards the ‘mainland’ western end of the Black Isle, with larger, mainly arable, units towards the eastern end. The main annual crops are wheat, oilseed rape, seed potatoes, malting barley and carrots. Christmas trees are a longer term crop. These high-value crops are intensively managed, which does not leave much room for ‘weeds’. Extensive Forestry Commission plantations, some dating from the 1920s, now cover the central spine of the Black Isle, known as the Mulbuie (Am Maol Buidhe; the yellow rounded hill). This was formerly common land, a mixture of moorland and scrub, used by the local population for grazing, building stone and peat- and turf-cutting for fuel, until appropriated by the landlords in1828, and now the property of the state.

The coast

Bottlenose Dolphin at Chanonry Point Craig Wallace/GEOGRAPH

Perhaps the most famous inhabitants of the seas around the Black Isle are the Moray Firth bottlenose dolphins, which now form the basis for a local wildlife tourism industry. As well as land-based viewing from Chanonry Point, specialist boat operators run tours in summer from Cromarty and Avoch (pronounced “Och”). The dolphins, along with the common (harbour) and grey (Atlantic) seals and harbour porpoises, which also inhabit the Firths, are studied by Aberdeen University from the Lighthouse Field Station at Cromarty. There is a chance of seeing these species from almost any coastal walk.

Along the wilder parts of the coastline, as from Rosemarkie north-eastwards, otter signs are frequently seen, although the animals themselves are more elusive. Walking this stretch, along the base of the cliffs, it is difficult to believe that you are within a stone’s throw (literally) of the intensive agriculture going on above. Just north of Rosemarkie, a rocky nose plunging directly into the sea renders this route impassable for a couple of hours either side of high tide. It pays to be first along after it clears, to catch any otter footprints in the sand before they are obliterated by other walkers!

Tidal section of coastline by Scart Craig Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

Because they are set back from the sea by the raised beach, the cliffs here are well-vegetated, with areas of mixed woodland, and scrub of blackthorn and elder. The songs of whitethroats and wrens seem to be amplified by the cliffs.

Coastal scene at Cairds Cave Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

Where the sandstone is calcareous, more unusual plants such as the rock whitebeam, bloody cranesbill, common rockrose, Spring cinquefoil, carline thistle and meadow and mossy saxifrages can be found.

Spring Cinquefoil Ro Scott

Other plants, such as deadly nightshade and henbane are thought be early garden escapes, having originated as medicinal herbs used by the monks at Fortrose. These sun-baked south-east facing cliffs support a population of the northern brown argus butterfly, whose larvae feed on the rock-rose. Where the cliffs are too sheer for plant growth, ledges are utilised by nesting fulmars and shags. Fulmars also nest practically in the village of Rosemarkie, on unstable cliffs eroded from deep glacial deposits forming steep valleys known as the Dens. Peregrines hunt along the cliffs, for rock doves and feral pigeons which roost in the caves. Near to the Eathie Burn was the only Black Isle site for the purple oxytropis, Oxytropis halleri. Unfortunately this stretch of cliff was planted with conifers some years ago and the few remaining plants have now been shaded out.

At the foot of the cliffs there is, in places, a narrow strip of sand dune vegetation with marram and lyme grasses, burnet rose, sand sedge, sea sandwort, common storksbill, purple milk-vetch and wild liquorice, Astragalus glycyphyllos. Where water trickles out of the sandstone, small patches of marsh occur, with hemp agrimony, ragged robin, glaucous sedge and a variety of orchids.

Munlochy Bay Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

In complete contrast to these rocky shores, the heads of the Beauly and Cromarty Firths, as well as Udale and Munlochy Bays (on the north and south sides of the Black Isle respectively) are gently-sloping, and offer huge expanses of intertidal mud and sand. It is here that enormous numbers of wildfowl and waders congregate in winter to exploit the rich feeding resources of shellfish and eel-grasses.

Udale Bay Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

These areas form part of the Cromarty Firth and Inner Moray Firth Special Protection Areas (SPA) designated under the European Birds Directive. They also qualify as ‘Wetlands of International Importance’ under the Ramsar Convention, because of the high numbers of migratory waterfowl which they support. The most numerous wintering wildfowl species are wigeon, teal and mallard but others, such as mute and whooper swans, shelduck, and red-breasted merganser, occur in smaller numbers. Further out in the firths, scaup, long-tailed duck and eider may be seen. Among the waders, oystercatcher, curlew, redshank, turnstone, ringed plover, dunlin, knot and bar-tailed godwit occur in good numbers.

Outlook from Udale Bay RSPB hide Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

The best viewing-point for wildfowl and waders, at the right state of the tide, is the RSPB hide, beside the B9163 at Udale Bay near Jemimaville. This hide looks out from the mouth of the Newhall Burn across the shallow bay. Beyond the mouth of the burn, where a variety of gull species (black-headed, common, herring, greater black-backed) are usually squabbling and preening, is an area of salt-marsh vegetation with some clumps of smooth cord-grass, Spartina alterniflora, which has persisted since being planted for coastal reclamation in the 1920s, and is much less invasive than its hybrid relative S. x townsendii.

In winter, the Black Isle spectacle par excellence is the daily commute of thousands of pink-footed and greylag geese between their roosts on the firths and feeding grounds on the farmlands. This uplifting sight and sound is not so popular with the farmers, though. In spring and autumn, the geese which spend their whole winter in the Black Isle are augmented by those on passage to or from more southerly wintering grounds.

Arable landscape

Corn marigold Ro Scott

The vast majority of the Black Isle landscape is dominated by agriculture. Where herbicide use is less rigorous, some small patches of corn marigold, and even smaller patches of cornflower, make an annual appearance. Roadside verges are garnished with a creamy froth of cow parsley, sweet cicely and meadowsweet flowers, followed by the blue and yellow of tufted vetch and meadow vetchling. These rough and untended patches support populations of field voles which feed the kestrels.

Black Isle winter scene of forestry and farmland Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

In spring the song of the skylark still fills the air, occasional pairs of lapwings attempt to nest, and brown hares cavort in the fields, but populations of grey partridge are struggling, and the corn bunting is now extinct. In most summers a small number of migrant quail are reported, usually identified by their ‘beep-be-deep’ calls from the depths of a cereal crop. In winter, mixed flocks of finches and buntings – linnets, redpolls, yellowhammers and sometimes snow buntings, scour the fields for spilled grain.

Flocks of rooks can be seen probing for leatherjackets and other invertebrates in the fields, sometimes accompanied by the smaller jackdaws. Traditionally subject to spring shooting of the ‘branchers’ - young which have left the nest but cannot yet fly, is it a coincidence that the noisy and bustling rookeries are now increasingly built in the villages (and hence protected from shooting) rather than the open countryside?

Rookery at Rosemarkie Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

The ‘ordinary’ crows are also interesting in that the Black Isle falls on the hybrid zone between the black and hoodie morphs. Mixed pairs produce a range of intermediately bicoloured offspring. The ubiquitous farm steadings provide nesting sites for swallows and house martins, and there is also a small population of barn owls. During times of passage in spring and autumn, a variety of upland bird species pass through the Black Isle on their way to and from the hills – golden plover, wheatear, and hen harrier. Of the predatory mammals, foxes, stoats and weasels are present but seldom seen. Large numbers of pheasants and some red-legged partridges are released for shooting, and such predators are not popular.

The neglected formal gardens of Rosehaugh Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

Around the large houses built by the 18th and 19th Century agricultural improvers, such as Rosehaugh (demolished in the 1950s), Newhall and Braelangwell, are policy woods and gardens from which a variety of exotic plants have escaped into the wild – winter heliotrope, lords-and-ladies, leopards bane and dame’s violet. Another legacy of the long history of agricultural ‘improvement’ in the Black Isle is that many of the boggy places and freshwater lochs have been drained. In very wet winters, the ghosts of some of these, such as the Manse Loch at Rosemarkie, appear as wet patches in the fields. Perhaps the best known casualty of the mania for drainage was the Alpine butterwort, whose only British site was the ‘Moss of Auchterflow’, a huge bog occupying the valley of the Killen Burn, which runs parallel to the central Mulbuie ridge. First discovered in 1831 (and suspected by some of not being genuinely native), a combination of drainage, tree-planting and the Victorian craze for plant-collecting saw the species’ demise by 1919. Although the Alpine butterwort has gone, the demise of the bog is not quite complete – its name lives on in the farms of Auchterflow, Bog of Auchterflow and Easter and Wester Strath of Auchterflow. Small remnants of the boglands remain, and may give some clue as to the appearance of this vanished tract of the wild Black Isle.

Heaths, Moorlands & Boggy bits

Grass of Parnassus, Belmaduthy Dam SSSI Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

The Black Isle moorlands and heaths are a curious mix of the acidic and the calcareous. Where water flows out from the more base-rich layers of the Old Red Sandstone, heather, deer grass and bog asphodel may grow in close proximity to calcicolous species. A good example of this can be seen at the in the Scottish Wildlife Trust Reserve of Belmaduthy Dam (NH643571), which is managed in partnership with the Forestry Commission, who own it. Here, heathland with juniper, willow bushes and pine trees is intersected by calcareous runnels in which grow black bog-rush, tawny sedge, carnation sedge, broad-leaved cotton grass and yellow saxifrage (at its lowest-altitudinal occurrence in eastern Scotland). In June and July the site supports a profusion of orchids including twayblade, coralroot, early marsh, Northern marsh, lesser butterfly and heath spotted, as well as other lime-loving plants such as globeflower, northern bedstraw and grass of Parnassus. The openness of the vegetation must be maintained by autumn grazing using a neighbouring farmer’s sheep or cattle. A recent discovery is the tiny snail Vertigo geyeri, which lives in the calcareous flushes and is thought to persist only in areas which have remained open since the end of the last ice age. Similar combinations of plant species are found in the SSSIs at Roskill and Braelangwell Wood, and hints of the richness of pre-improvement Black Isle vegetation can be glimpsed in numerous small forgotten pockets among the forestry plantations and fields.

Woodlands & forestry

Simons Loch, Monadh Mor SSSI Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

The unusual juxtaposition of the acidic and the calcareous continues into the woodlands. A Scots pine wood with an understorey of juniper but ground flora including hair sedge, Alpine meadow-rue and black bog-rush, as found at Braelangwell Wood, certainly strikes one as peculiar. The most extensive natural pinewood is the Monadh Mor (Big Moor), towards the western end of the Black Isle. This is designated as an SAC under the Habitats Directive, for its bog woodland, which has affinities with the boreal taiga. The attractions here include: kettle-hole lochs and pools with bottle sedge and bog-bean; Sphagnum lawns through which creeps the small cranberry; and hare’s-tail cottongrass bog.

More conventional pinewood remnants can be found among the forestry plantations, many of which are also of Scots pine, and provide a reasonable facsimile of native pinewoods. Here, the creeping lady’s tresses orchid, chickweed wintergreen and lesser wintergreen can be found among carpets of blaeberry. Recently a population of the delightful twinflower has been discovered.

Many exotic conifers have also been planted, including Sitka and Norway spruce, lodgepole pine, Douglas fir, larch and Western hemlock. These large blocks of coniferous woodland support populations of red squirrel and pine marten, crossbills, goldcrests, siskins, crested tits and even the occasional capercaillie. Although unsuitable to host a permanent population of caper, the Black Isle woods form part of the range of the East Ross population.

Beech in Drummondreach Oakwood Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

The deciduous woodlands comprise a variety of oak, ash, elm and birch, depending on the soil type. At the Drummondreach Oakwood SSSI, near Ferintosh, the soils are acidic and oak is dominant.

Fairy Glen RSPB Reserve, Rosemarkie Julian Paren/GEOGRAPH

The Fairy Glen RSPB Reserve at Rosemarkie is more calcareous with ash and elm predominant, along with sycamore, beech and other introductions. In spring the woodland floor is carpeted with bluebells, wood anemones, wood sorrel, lesser celandines, and in places, the tiny town-hall clock or moschatel.

Moschatel or Town-hall Clock Ro Scott

The burn here is one of the few places where you may see dipper and grey wagtail. Of the woodland mammals, badgers are less common in the Black Isle than might be expected. Their setts are found only where glacial deposits of sand and gravel lie on top of the sandstone, presumably because the underlying soils are too shallow or waterlogged for a comfortable underground existence. Roe deer are frequently seen feeding in the fields early in the morning, but retire to the numerous wooded gullies or ‘dens’ once human activity starts for the day.

Red Kite Christine Matthews/GEOGRAPH

The re-introduced red kites breed well in the Black Isle and are a joy to watch from the roadsides (but preferably not while you are driving) as they dance overhead. Detailed studies by the RSPB have shown that unfortunately the population is not thriving, due to persecution of the young birds after they disperse to other parts of Scotland before reaching breeding age (when those that survive return to their natal area). Of the other breeding raptors, buzzards are common, particularly where there are rabbits, and tawny owls are more often heard than seen. Although freshwater lochs are few and far between, the short flying-distance between the woods and the Firths enables ospreys to nest inland but feed from the sea.

Wildlife recording

Peat coring Ro Scott

If you are interested in the wildlife of the Black Isle, whether as a resident or a visitor, you could make a contribution to our knowledge, by recording what you see. There are many local groups and societies to whom you can send your observations. All we need are the four components of a record: who you are; what you saw; when and where you saw it, preferably with an OS Grid Reference.

The Black Isle falls within the remit of the Highland Biological Recording Group, whose members record a great variety of different types of wildlife. HBRG regularly submits its records to the National Biodiversity Network Gateway, https://data.nbn.org.uk/ and has published Atlases of Highland butterflies (with the local branch of Butterfly conservation), Bumblebees, Mammals and Ants, all of which include coverage of the Black Isle. http://www.hbrg.org.uk/index.html

Vascular plant botany is well-covered, with a published flora (Duncan, 1980) and a more recent Checklist (Ballinger & Ballinger 2017) by the formally-appointed BSBI (Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland) Vice-Country Recorder http://bsbi.org/easter-ross . Inverness Botany Group http://www.invernessbotanygroup.com/ is also active in the Black Isle, and elsewhere!

Bird-life is similarly well studied, with the annual Highland Bird Reports published by the local SOC (Scottish Ornithologists Club) Group http://www.the-soc.org.uk/whats-on/local-branches-2/highland/ , organised monitoring in the form of WEBS (Wetland Bird Survey) counts and Breeding Bird Surveys by local BTO (British Trust for Ornithology) members, and the activities of the RSPB (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds) members’ group http://www.rspb.org.uk/groups/highland/about/ and Highland Ringing Group.

Many other local societies, such as the Highland branch of Butterfly Conservation http://www.highland-butterflies.org.uk/ , Tain http://tainfieldclub.org.uk/ , Inverness http://www.invernessfieldclub.org.uk/ and Dingwall Field Clubs http://www.spanglefish.com/dingwallfieldclub/ and the Scottish Wildlife Trust North of Scotland Members’ Group http://scottishwildlifetrust.org.uk/local-member-group/north-of-scotland/ sometimes conduct field trips to the Black Isle. The more demanding groups of organisms, particularly the invertebrates and lower plants, depend on sporadic visits from itinerant specialists, and are patchily recorded. If you have a specialised interest, or are caught out by bad weather in the hills, why not visit the Black Isle? - There are undoubtedly still new discoveries to be made.

Ro Scott

Highland Biological Recording Group

Further reading

Ballinger B & Ballinger B (2017) Easter Ross Plant Checklist (VC 106). Available for download from: http://bsbi.org/easter-ross

Duncan, UK (1980) Flora of East Ross-shire. Botanical Society of Edinburgh.

Miller, H (1841) The Old Red Sandstone. Johnstone and Hunter, Edinburgh.

Scottish Ornithologists’ Club, Highland Branch. Highland Bird Report (2014). (Reports produced annually) available from http://www.highlandbirds.scot/highland-bird-report.html

Willis, D (1989) Discovering the Black Isle. John Donald, Edinburgh.